Introduction

Historically, the question of authorship of the Epistle to the Hebrews has revolved around the Apostle Paul. Essentially, there have been two questions that have been applied: did Paul pen this letter; if not which known person, within the Pauline circle, did? Even though, from the time of the early church, there exists a long list of potential candidates[1], this paper will only attempt to discuss three of the strongest candidates. In examining recent pieces of research, it seems that these three are: Paul, Luke, and Apollos. However, for the first two, the issue of authorship is more complex. There are a few theologians that are considering the possibility that Hebrews is a collaborative effort between Paul and Luke. Therefore, the case for each of them being the independent author, as well as the collaborative hypothesis, will be addressed. In doing so, internal evidence from Hebrews, as well as external evidence, will be employed. By the end of this discussion, it will be contended that, of the possible authors, Apollos is the best possible candidate for authorship of Hebrews.

Let us consider, for a moment, why this quest is important. Throughout history, the church has encountered periods where the attribution of authorship was given, without question, to Paul. There have, also, been periods, in which, attribution was much less certain. Furthermore, there have been periods, in which, one collection of churches was certain, while others were not. However, in all of these periods, Hebrews has been regarded as useful in matters of faith. In other words, historically, it has been considered canonical. Why, then, is this question so prevalent in discussion of this epistle? Authorship is important to us, if for no other reason, because it contributes to the historical-cultural context of the epistle. Correctly understanding this context is helpful to correctly understand some of the content of Hebrews.[2] Furthermore, getting it wrong in this department has the potential of calling into question the nature of the canon, itself. In other words, if Paul, another apostle, or a close associate of an apostle did not author Hebrews, and we continue to recognize it as canonical, what else might be canonical and authoritative?

The New Testament Canon

Questions akin to the previous were at play in the early church during the process of considering what texts were canonical. During this time, there were a number of controversies and erroneous characters that helped to motivate the early leaders to consider this issue. For instance, it was not the church leadership, nor a Christian, that developed the first list of canonical writings of the New Testament. Instead, an early gnostic-dualist, Marcion, purveyed a list that included an edited version of Luke’s gospel and ten Pauline letters, that excluded the pastoral epistles.[3] Marcion also rejected the Old Testament, New Testament-era teachings directly linked to the Old Testament, as well as any linkage between Jesus and the Creator God of the Old Testament. Furthermore, he rejected the Trinitarian view of God. In short, Marcion was a heretic.[4] A different type of problem sprang up at about the same time; one that was initially intended to be a reforming movement. However, they went too far in emphasizing participation with the Holy Spirit to gain revelation concerning the things of God.[5] It was a common fear amongst the church leadership that this group (called Montanists) would rebut what was known from the written testimony of the early followers of Jesus.

The church’s response to these two problems, as well as others, was to move to close the canon. However, this was not decided in a single ecumenical or local council. Rather, this was a process that took time to gain a generally universal acceptance throughout the churches. The issue that was faced during this process was that each local church had their own codex of writings that they used. While much of the content of these was the same throughout the churches, not all of it was. Therefore, two criteria became useful for the churches to recognize[6] what was authoritative: apostolicity (the author was an apostle or a very close associate of an apostle) and spiritual usefulness (the voice of God “spoke” through a document).[7] Being that this is recognized as a process, it should come as no surprise that archaeology and biblical studies have discovered and revealed a number of early canons; many of which differ considerably on what was rejected versus recognized—i.e. the Epistle to the Hebrews, in many early canons can be shown to be either disputed (recognized by some), recognized, or not considered at all.[8] Later, it will be maintained that one of the reasons for the assertion of Pauline authorship was to help guarantee this epistle’s entry into the New Testament canon.

Internal Evidence from Hebrews

The mystery of authorship, historically, has been stoked by the fact that the author fails to identify himself. Contrary to what one would normally find in the prologue or introduction of a New Testament text, there is no personal introduction. Neither does the author give anyone, other than the original recipients, any clear idea who he may be. However, throughout the body of the epistle, the author provides for us a set of clues and hints about his attributes. This section will address what we can learn about the author from the contents of Hebrews, itself.

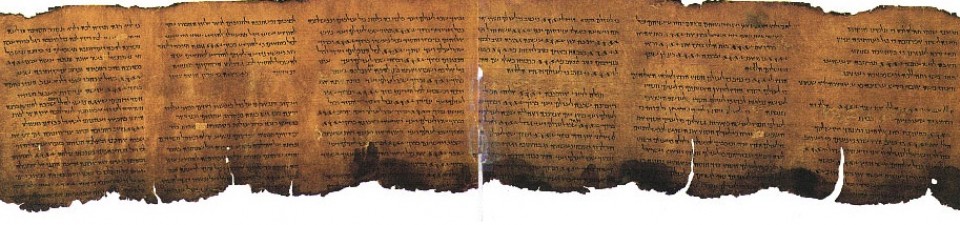

The author seems to be well-versed in the Greek translation of the Old Testament, the Septuagint (LXX). One study on Hebrews counted twenty-four instances in which the author quoted, directly, form the Old Testament. Further, there may be five other locations, in which the author speaks about an Old Testament verse without actually quoting it. At points in antiquity, some have attempted to assert that Luke translated for Paul from Hebrew or Aramaic into the Greek form of Hebrews. However, as Kistemaker points out, the author “never corrects the Greek translation to make it conform to the Hebrew text (sic).”[9] Therefore, the translation hypothesis fails, in this regard. There is no reason, within the reading of Hebrews, to believe that the author was familiar with the Hebrew version of the cited Old Testament scriptures.[10]

The author seems to be comfortable with specific types of first-century rabbinical interpretive methods. Two examples, discussed by Guthrie, are the verbal analogy (gezerah shawah) and the lesser-to-greater (qal wahomer) argumentation.[11] In Hebrews 4:3 and 4:4, we note that the author connected the concept of entering God’s “rest” between these two verses by comparing the those who will enter into it (those who believe, the faithful) and those who will not enter into it (those who are under God’s wrath, the disobedient). In Hebrews 2, the author provides a supreme example of the lesser-to-greater argument. Here, he exhorts his readers not to neglect the message of the gospel by drawing a line from his readers to the Exodus generation. The Exodus people had neglected God’s message, that was mediated to them via angels, thus, God refused to let them enter into His rest. Therefore, they “must pay much closer attention” (v. 1a)[12] to the message mediated to them by God’s Son. This is because if God punished those who neglected the lesser message, how much more will He punish those who neglect the greater message.

The author comes across as a trained rhetorician which translates well into being a preacher. Scholars have long regarded Hebrews as a text written in sermonic form. Guthrie believes that there are numerous instances within Hebrews that resemble sermons found within ancient Hellenistic synagogues. Furthermore, within Hebrews 13:22, the author appeals to his readers to, “bear with my word of exhortation,” which seems to be a clear indication of his sermonic mood. Furthermore, his skill in explaining the LXX and his rich vocabulary usage point to the possibility that the author was well educated. Lane points out that many Hebrews scholars believe that the author’s education may be reflective of that which was provided in private schools of rhetoric in first-century Alexandria, akin to that of Philo.[13] In reference to vocabulary usage, of the nearly five-thousand words found in Hebrews, the author employs one-hundred and sixty-nine hapax legomena (words or word forms that occur only once; unique words) when compared to the rest of the New Testament.[14] Furthermore, he may have been the only New Testament author to employ classical Greek versus the Koine version of the language.[15] Not only does this point to a superior level of education, but it also gives us a clue to the overall eloquence of this man. It is highly likely that this man would have been a highly respected oratorical speaker, who was able to defend his religious views quite well and with ease from the LXX.

Finally, the author seems to have been acquainted with Paul, or, at least, Paul’s arguments and legacy. This assumption is partly based upon the long-held belief that Paul was the author of this epistle. However, internally, there are a number of themes that can also be found within the Pauline corpus. Hebrews is entrenched with the new covenant theme, which is also found within 2 Corinthians 3. Also, both Hebrews and Paul rely on aspects of the Old Testament law to make their points.[16]

At this point, more could be said of the author (Was he a witness to Jesus’ resurrection; how did he receive the gospel; and, external evidence?). However, these other points will be reserved for the discussion concerning the specific candidates.

Paul

The most obvious candidate is the person who, other than Jesus, is featured most prominently within the New Testament. One of the strongest early proponents of Pauline attribution was from the early head of the catechetical school in Alexandria, Pantaenus. Black comments that, “Pantaenus entertained no doubts about…Pauline authorship (sic).”[17] However, in attempting to explain the absence of Paul’s characteristic introduction in Hebrews, Pantaenus comes up with this explanation,

But now, as the blessed elder said, since the Lord being the apostle of the Almighty, was sent to the Hebrews, Paul, as sent to the Gentiles, on account of his modesty did not subscribe himself an apostle of the Hebrews, through respect for the Lord, and because being a herald and apostle of the Gentiles he wrote to the Hebrews out of his superabundance.[18]

Essentially, Pantaenus is claiming that Paul failed to claim authorship because he wasn’t sent to the Jews, but to the Gentiles.

Within the Alexandrian school, two others would fully claim, or claim with a touch of reticence, Pauline authorship—Clement of Alexandria and his pupil, Origen. Clement was the first to make the assertion that, while Paul did write Hebrews, he did so in Hebrew or Aramaic, and had Luke translate the text into Greek. While being a variant from Pantaenus’ reasoning, Clement made this assertion for a similar reason. He believed that Paul may have feared that the Jews would have been averse to an epistle from his hand. Thus, having Luke translate it into Greek would have helped prevent the Jews from rejecting it, especially if Luke included his own style in the translation.[19]

Origen while seemingly giving credit to Paul, “if any church hold that this epistle is by Paul, let it be commended for this (sic),”[20] also lists two other possible candidates: Luke and Clement of Rome (who was known to have cited from Hebrews numerous times). It seems that Origen recognized stylistic differences between the Pauline corpus and Hebrews. However, it seems that he still believed that the ideas were Paul’s. How they were placed into Hebrews, he wasn’t sure, “God knows”.[21] The Chester Beatty Papyrus (P46), which has been dated to A.D. 200, also seems to credit Paul as the author. As, within it, Hebrews occurs just after two Pauline epistles: Romans and 1 Corinthians.[22]

For the most part, the Eastern churches (likely due to the influence of the three previously discussed Fathers) were quick to accept Pauline authorship and persevere in this view. However, in the West, there was a long period of silence, or a list of other possible authors, regarding this topic. However, this, in no way, would imply that they viewed Hebrews as non-canonical or disputed its canonicity. In the West, it was widely used within the churches.

It wasn’t until the fourth century that we find influential Western Fathers beginning to suggest and support Pauline authorship. Likely, the first in the West to accept this position was Hilary of Poitiers, who was attempting to bridge the gap between the Eastern and Western churches, with regards to Hebrews.[23] Not long after, the great doctor of the Latin Church, Augustine of Hippo-Regius, as well as Jerome, the translator of the Latin Vulgate, both supported the Pauline position. However, it is known that Jerome, at least, did so with reservation. According to Jerome, “it makes no difference whose it is, since it is from a churchman, and is celebrated in the daily readings of the Churches (sic).”[24] In other words, although he was willing to accept Paul, it seemed more important to him that it was recognized as authoritative in matters regarding faith. This must have been the general consensus view in the West, prior to Augustine and Jerome, as it is known that Hebrews was used by Irenaeus (who was operating in the West, at Lyon, and is known to have dissented from the Pauline view) to refute Gnosticism.[25]

Perhaps it was the recognized authority of Augustine that convinced the churches in the West to accept Paul. What is known is that the councils of Hippo and Carthage (A.D. 393 and 397, respectively) both recognized Hebrews as authoritative, but failed to group it within the Pauline corpus of thirteen epistles.[26] However, not long after Augustine’s Pauline recognition, the fifth council of Carthage (A.D. 419) recognized, not thirteen, but fourteen Pauline epistles, as it was decided that Hebrews belonged to Paul.[27]

Critique of Pauline Attribution

There are a number of reasons why it is understandable that one might view this anonymous work as Pauline. One of these is the voluminous body of the Pauline works. Also, Paul was one of the most active apostles in establishing, nurturing, and directing churches. Finally, Paul operated in the East and possibly even the West (in his epistle to the churches in Rome, he confessed his desire to use Rome as a launching point to move West). However, there are a number of problems with this view.

First, on what authority and/or evidence did Pantaenus or Clement of Alexandria base their initial assertions? It seems that they have based their whole view on a set of contrived ideas of why Paul either failed to include his name, a classic benediction, or a closing salutation. Metzger offers the idea that Pantaenus was attempting a “conciliation, made necessary by the existence of two types of the corpus Paulinum, one with and the other without the Epistle to the Hebrews.”[28]

Although Origen congratulates the churches who adhere to the Pauline view, his writing reveals that even he didn’t seem convinced enough to directly attribute the apostle, “But who wrote the epistle, in truth, God knows.”[29] Furthermore, although P46 seems to give credence to Paul, an earlier manuscript, the Muratorian Canon (A.D. 175), doesn’t even include Hebrews.[30] Also, we need to be reminded of the early Western ignorance on this topic. Clement of Rome, while quoting from Hebrews, never cited Paul as the author, as was customary. Hippolytus, Polycarp, and Irenaeus all followed this pattern of recognizing the spiritual authority of Hebrews but excluded any notion of apostolicity to it.[31] There is no reason to suspect that Paul had Luke translate a copy of Hebrews from the Hebrew language to the Greek, nor does the construction of Hebrews support this idea (see the previous discussion about internal evidence). Taken together, these points seem to cast much doubt on the external evidence as being pro-Paul.

Why, then, did the Eastern churches seem to be so quick to accept the Alexandrian view of Pauline authorship? More than likely, the answer to this question is directly related to its inclusion in the canon. By now, it should be clear that the churches throughout the Roman Empire viewed Hebrews as authoritative based upon its voice and content. Furthermore, this epistle was an important tool in the refutation of a number of heresies—i.e. Irenaeus’ fight with Gnosticism and Athanasius’ defense of orthodoxy against the Arian position.[32] However, the position of the church, with regards to what made orthodoxy, could have been weakened by its enemies by attacking this epistle. Unless, of course, an apostle had written it. Furthermore, Kistemaker informs us that, within Alexandria, a book or epistle was often denied or contested canonicity apart from apostolic authority.[33] Therefore, in attaching Paul to Hebrews, the Alexandrian leadership, followed by the churches in the East, ensured Hebrews’ acceptance into the canon.

Internal issues also plague the Pauline hypothesis. There are a number of internal parallels between Hebrews and the Pauline corpus. Black displays a large body of these internal affinities.[34] However, there also exist quite a divergence. Examining common themes, it becomes obvious that discussions of the Old Testament law are important and central to both Paul and Hebrews. However, the concern of each, within this theme, is quite different. Within Hebrews, the author masterfully constructs an argument around the temple cultus. In Paul, however, his discussion is more focused upon circumcision.[35] Another theme that is prominently featured in both is faith. Within the eleventh chapter of Hebrews, the famous roster of the faithful can be found. Within the fourth chapter of Romans, Paul expounds on the value of trusting in the promises of God. While both of these operate around the theme of faith, these authors’ definition of the theme is not the same.[36] For the author of Hebrews, faith amounts to assurance and conviction, which leads to faithful living. In Romans, Paul seems to be communicating that faith in God’s acts makes us righteous. One of the most central themes in the author of Hebrew’s argument is the high priest Christology.[37] However, this theme is not unique to Hebrews, one can also find it within Romans, “Christ Jesus…who is at the right hand of God, who indeed is interceding for us” (8:34). However, this theme is also evident within Mark, “Jesus…was taken up into heaven and sat down at the right hand of God” (16:19).

In contrast to Black, Kistemaker provides for us a lengthy list of other internal inconsistencies: Greek forms (classical v. Koine), usage of the Psalms composition differences, and vocabulary differences, amongst others.[38] The death-knell for the Pauline hypothesis, however, exists in how the author of Hebrews describes himself, “It [the gospel] was declared at first by the Lord, and it was attested to us by those who heard (sic)” (2:3b). In other words, the author identifies himself as a second-generation believer, having received the gospel from the testimony of the apostles. In contrast, Paul claimed that he, “did not receive it from any man, nor was I taught it, but I received it through a revelation of Jesus Christ (sic)” (Gal. 1:12). Therefore, Paul could not have been the author of Hebrews; we will have to consider other alternatives.

Luke

Generally, Lukan authorship has been submitted due to a number of factors. First, the weak case for Pauline attribution. Second, some internal consistencies between Hebrews and Luke-Acts. Third, Luke’s close association with Paul may account for the apparent “Paul-ness” of Hebrews. Finally, the fact that we actually have Luke’s writing to compare with Hebrews.

Allen does an excellent job of defending this position. For him, lexical and stylistic similarities between Luke-Acts and Hebrews make the case. For example, much of the vocabulary that occurs in Hebrews is also found within Luke-Acts (67.6%). More specifically, fifty-three of these words are unique to Hebrews and Luke-Acts.[39] Following this, Allen provides a list of specific vocabulary, and phrases, that are found within Hebrews, non-Lukan writings, as well as, Luke-Acts. Within this list, he discusses how they are used.[40] Allen’s list makes a strong case for similar linguistic patterns between Luke-Acts and Hebrews, specifically.

Allen moves on to discuss some of the thematic similarities between Luke-Acts and Hebrews. He points out that both display an exalted Christology that emphasizes the deity of Christ. Next, Allen points out that only in Luke-Acts and Hebrews is the “attainment of perfection…[accomplished] through his suffering and death (sic).”[41] Luke-Acts and Hebrews use a Christological title that is unique to them, archegos, which only appears in Hebrews 2 and 12 and Acts 3 and 5. While Hebrews more fully develops the high priesthood of Christ theme, it is not absent from Luke-Acts. In his Gospel, Luke speaks of the anointing of Jesus, which is an allusion to the high priestly ministry. Furthermore, along this same theme, Luke provides an example of Jesus giving a high priestly prayer, in Luke 24:50-51.[42]

Critique of the Lukan Proposal

Allen’s argument is not compelling enough for all. Cockerill points out that the literary form of Hebrews argues against Allen’s Lukan hypothesis. Hebrews is recognized to be in sermonic form. However, as Cockerill points out, Luke-Acts fails to provide any evidence that Luke was ever directly involved in the exercise of preaching. Furthermore, similar vocabulary is no guarantee of similar authorship.[43]

There are other reasons to deny Luke’s involvement in Hebrews. Hebrews leans heavily upon quotations and citation from the LXX; which were the Greek translation of the Jewish scriptures. Although some have recently attempted to argue that Luke may have been a Jew, there is still no compelling reason to hold to that position.[44] Therefore, it is not likely that a Gentile, such as Luke, could have had the command of the LXX that the author of Hebrews seems to have had. Also, the author of Hebrews employed distinctly Jewish interpretive methods of the LXX. To this, we may attach the previous critique. Why would a Gentile know how to apply these? Therefore, Lukan authorship, while an intriguing idea, is doubtful.

Apollos

Apollos is a recent submission, who was first proposed by Martin Luther after having rejected the traditional Pauline view. According to Guthrie, arguments favoring Apollos take three basic forms, one of which we have already performed. First, arguing against other possible authors (Paul and Luke were both argued against). Second, internal evidence that corresponds to what is known about Apollos. Third, other correspondences that have been viewed as questionable.[45] One of the charges made against this view is that not much is known about Apollos; further, we have no known texts authored by Apollos to compare with Hebrews. These are unfortunate truths that force those who hold to this view to refute the other hypotheses, in order to support Apollan hypothesis. In other words, one of the strengths of asserting Apollos comes from the inherent weaknesses of the other alternatives.

New Testament Data on Apollos versus Characteristics of Hebrews

The author seems to be a talented expositor within the Hellenistic synagogue style. Furthermore, the author, as Hebrews 13:22 tells us, has written a “word of exhortation.” Guthrie maintains that this is a clear indication that Hebrews is sermonic.[46] The author uses many quotations directly from the LXX, this draws upon the assertion that the author may have roots in the Hellenistic synagogue. Along with this, the author draws upon two forms of interpretation that are specifically Jewish: qal wahomer and gezerah shawah.[47] Thus, he didn’t just know the LXX, but he could also interpret, and apply them to the experience of his readers. The author was, apparently, highly educated within the rhetorical style. This education is also displayed in his advanced use of his Greek vocabulary and form. Specifically, his use of rhetoric, Greek, and vocabulary seem to rival that which was taught within the schools of Alexandria.[48]

In Acts 18:24, Luke refers to Apollos as an “eloquent man,” which is a title that demonstrates the bearer commands a mastery of rhetoric and speech. Furthermore, Paul, in 1 Corinthians 3:4, provides an indication of Apollos’ speaking and preaching ability, in pointing out that some follow his teaching and by comparing him to Peter. It is certain that Apollos originated in Alexandria and that he was known by Paul and other associates of Paul. Finally, it is clear to us that Apollos was a Hellenistic Jew, who may have been familiar with Jewish forms of interpretation, as well as the LXX.[49] This comparison of what we know about Apollos with what we know about the author of Hebrews, next to the fact that Pauline or Lukan attributions are weak, at best, Apollos emerges as the best possible candidate. However, this position is not without flaw or its share of criticism, as the opening paragraph of this section highlights.

Conclusion

External and internal inconsistencies, especially the comparison of Hebrews 2:3 with Galatians 1:12, fatally damage the Pauline position. Some have proposed Luke as the author. However, no one has, as of yet, conclusively displayed that he was anything but a Gentile. This makes the fact that Hebrews draws heavily upon Jewish elements (LXX and interpretive methods) highly unlikely that Luke is the author. Apollos best fits what is known, via internal evidence, about the author. Therefore, while not being free of problems, it is believed that Apollos is the most likely candidate to fill the identity of the author of the Epistle to the Hebrews.

Bibliography

Allen, David L. Lukan Authorship of Hebrews. Nashville, TN: B&H Academic, 2010. Kindle Electronic Edition.

—. “The Authorship of Hebrews: The Lukan Proposal,” Faith and Mission 18:2 (Spring 2001): 27-37.

Allison, Gregg R. Historical Theology: An Introduction to Christian Doctrine. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2011.

Black, David Alan, “Who Wrote Hebrews? The Internal and External Evidence Reexamined,” Faith and Mission 18:2 (Spring 2001): 3-22.

Carson, D. A. & Moo, Douglass J. An Introduction to the New Testament, 2nd ed. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2005.

Cockerill, Gareth Lee. The New International Commentary on the New Testament: The Epistle to the Hebrews. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2012.

Dunn, James D. G. “Pauline Legacy and School” Dictionary of the Later New Testament & Its Developments: A Compendium of Biblical Scholarship, ed. Ralph P. Martin & Peter H. Davids, 883-93. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1997.

Dyer, Bryan R. “The Epistle to the Hebrews in Recent Research: Studies on the Author’s Identity, His Use of the Old Testament, and Theology,” Journal of Greco-Roman Christianity and Judaism 9 (2013), 104-31.

Guthrie, George H. The NIV Application Commentary: Hebrews. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1998.

—. “The Case for Apollos as the Author of Hebrews,” Faith and Mission 18:2 (Spring 2001): 41-54.

Jervell, Jacob. The Theology of the Acts of the Apostles. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press,1996.

Kistemaker, Simon J. “The Authorship of Hebrews,” Faith and Mission 18:2 (Spring 2001): 57-67.

Lane, William L. “Hebrews,” in Dictionary of the Later New Testament & Its Developments: A Compendium of Biblical Scholarship, ed. Ralph P. Martin & Peter H. Davids, Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1997: 443-58.

Metzger, Bruce M. The Canon of the New Testament: Its Origin, Development, and Significance. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 1987.

Endnotes

[1] David L. Allen, Lukan Authorship of Hebrews (Nashville, TN: B&H Academic, 2010), Kindle Electronic Edition, Location 296-307.

[2] Bryan R. Dyer, “The Epistle to the Hebrews in Recent Research: Studies on the Author’s Identity, His Use of the Old Testament, and Theology,” Journal of Greco-Roman Christianity and Judaism 9 (2013): 112.

[3] D. A. Carson & Douglas J. Moo, An Introduction to the New Testament, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2005), 732.

[4] Gregg R. Allison, Historical Theology: An Introduction to Christian Doctrine (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2011), 41-2.

[5] Ibid., #43.

[6] This is an important distinction versus “determine.” As it is recognized that God, though His Spirit, and through the package of human language, grammar, culture, etc., inspired the text of the New Testament writings. The early church didn’t determine what God was saying, they recognized what He was saying.

[7] Allison, 42.

[8] Hebrews is missing from the Muratorian canon (A.D. 170) and Eusebius’ canon (~A.D. 250), disputed in Origen’s canon (~A.D. 325), and recognized as canonical in Athanasius’ canon (A.D. 367).

[9] Simon J. Kistemaker, “The Authorship of Hebrews,” Faith and Mission 18:2 (Spring 2001): 60.

[10] Ibid.

[11] George H. Guthrie, The NIV Application Commentary: Hebrews (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1998), 25

[12] Unless otherwise noted, all biblical passages referenced are in the English Standard Version.

[13] William L. Lane, “Hebrews,” Dictionary of the Later New Testament & Its Developments: A Compendium of Biblical Scholarship, ed. Ralph P. Martin & Peter H. Davids (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1997), 444.

[14] David L. Allen, “The Authorship of Hebrews: The Lukan Proposal,” Faith and Mission 18:2 (Spring 2001), 28-9.

[15] Kistemaker, “Authorship of Hebrews,” 60.

[16] James D. G. Dunn, “Pauline Legacy and School” Dictionary of the Later New Testament & Its Developments: A Compendium of Biblical Scholarship, ed. Ralph P. Martin & Peter H. Davids (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1997), 891.

[17] David Alan Black, “Who Wrote Hebrews? The Internal and External Evidence Reexamined,” Faith and Mission 18:2 (Spring 2001): 17.

[18] Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 6.14.4, taken from Kistemeyer, “Authorship of Hebrews,” 57.

[19] Black, “Who Wrote Hebrews?”.

[20] Gareth Lee Cockerill, The New International Commentary on the New Testament: The Epistle to the Hebrews (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2012), 5.

[21] Ibid.; and Black, 18.

[22] Kistemaker, “Authorship of Hebrews”, 58.

[23] Cockerill, Epistle to the Hebrews.

[24] Taken from, Kistemaker, “Authorship of Hebrews,” 59.

[25] Black, “Who Wrote Hebrews,” 19.

[26] Cockerill.

[27] Black, “Who Wrote Hebrews”.

[28] Bruce M. Metzger, The Canon of the New Testament: Its Origin, Development, and Significance (Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 1987), 130.

[29] Taken from Cockerill, Epistle to the Hebrews.

[30] Allison, Historical Theology

[31] Kistemaker, “Authorship of Hebrews.”

[32] Kistemaker, “Authorship”; Cockerill, Epistle to the Hebrews.

[33] Kistemaker.

[34] Black, “Who Wrote Hebrews,” 4-11.

[35] Dunn, “Pauline School”.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Kistemaker, “Authorship of Hebrews,” 60-2.

[39] Allen, “The Lukan Proposal,” 28-9.

[40] Ibid., #29-32.

[41] Ibid., #33.

[42] Allen, “The Lukan Proposal,” 34-6.

[43] Cockerill, Epistle to the Hebrews, 9.

[44] Jacob Jervell, The Theology of the Acts of the Apostles (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 5.

[45] George H. Guthrie, “The Case for Apollos as the Author of Hebrews,” Faith and Missions 18:2 (Spring 2001), 49.

[46] Ibid., #50.

[47] Ibid., #51.

[48] Ibid., #51.

[49] Lane, “Hebrews”; Guthrie, “Apollos,” 52.